Battle for The Valley revisited

I thoroughly enjoyed Battle for The Valley. As a relative newcomer to London and Charlton Athletic, I found it a great way to be introduced to the history of the club and thought the writer provided a good balance between the finances, the politics and the play on the pitch. Great writing, a great story and his own involvement in the drama was pitched just right. Partisan, yes, but as far as I can read it, fairly played. The book has plenty of photos and it was just a lot of fun to read, getting to know the stories and the characters behind the history. Reading over the past week made me wish the season was starting sooner. Congratulations to Rick for a great summer read.

- blackheathcanuck on the Charlton Life message board

Read Ben Hayes' review from the News Shopper website and the feature from the Isle of Thanet Gazette.

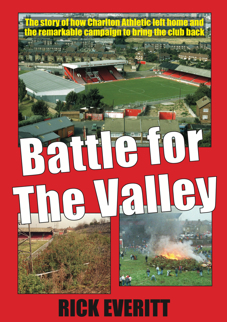

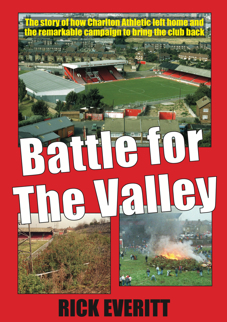

The revised and extended paperback edition of Battle for The Valley was published in early July 2014 after being unavailable for more than 20 years. Now running to 320 pages, Rick Everitt's fully illustrated history of Charlton's home since 1919, the 1985 move to share Crystal Palace's Selhurst Park and the struggle to return to SE7 boasts three brand new chapters, a new introduction and 50 additional pictures, many of which are in colour.

As well as the epic battle to get home, which saw the Mercury collect a 15,000-signature petition, fans rack up 14,838 votes as the Valley Party in the Greenwich local elections of 1990 and then stump up over £1m to complete the work when the club ran out of money, it also tells the tale of Charlton's previous expedition to Catford in 1923.

You can order it direct from this website below.

We are currently offering this book at a special price of £9 (£6 to VOTV subscribers) for a limited period. To purchase at this special price, please use the icon on the front page of this website - not the standard price one below.

RICK EVERITT discusses the new extended edition of Battle for The Valley and the challenges involved in putting the book back together.

Identity is at the core of current political debate about immigration, Scottish nationalism and the European Union. It has been at the heart of arguments at Cardiff City and Hull City over team colours and the club name.

It also lurks beneath some of the unease about the Belgian influx that has so far characterised Roland Duchâtelet’s ownership of Charlton Athletic.

In reality, the club is always more than the people who own it or work for it at any particular time, which is one of the lessons that we ought to draw from another challenge to its identity a quarter of a century ago.

The 1985 move to share Crystal Palace’s Selhurst Park proved to be a watershed in the club’s history, but not in the way that it seemed at the time.

While both Scunthorpe United and Walsall moved to new stadia during Charlton’s exile, the concept of changing home grounds was completely unfamiliar back then, even when the new venue did not obviously belong to another club.

But what had appeared likely to extinguish Charlton’s identity ultimately served to strengthen it, even if only because of the backlash it provoked.

I had plenty of opportunity to revisit these issues this year while I worked on the new 320-page paperback Battle for The Valley, which came out in July. The book was originally published in December 1991 with the club still stranded at Upton Park and unable to afford the work required to return to Floyd Road.

Its premature appearance came about because the homecoming had been planned to take place that autumn and I had taken more than 300 advance subscriptions. There was also some doubt if the club would ever get back.

My obvious task this time was to complete the story up to and including December 5th, 1992.

In practice, however, the book had to be rebuilt from scratch, including sourcing all the historic and more modern pictures again, as well as scanning in and recompiling the original text, using optical character recognition software.

Former club photographer Tom Morris put in many hours locating, scanning and supplying images old and new, while Steve Bridge and Michael Whelan – two more original collaborators – were more than helpful in digging out some of the other pictures.

I then had to decide how far to remain faithful to my original judgements about people and events. For the most part, it appeared to me that it would be wrong to revisit the conclusions I had reached at the time, even if one or two of them jarred in the light of later experience.

It seemed appropriate, for example, to leave in the record that in 1987 the newly acquired Charlton Athletic training ground at Sparrows Lane could be considered “the best in the League”, even if it probably wasn’t then and certainly isn’t now.

On the other hand, the internet has provided considerable additional opportunities for research since 1991.

For example, I learned for the first time that Edwin Radford – probably the most significant force in the club joining the Football League in 1921 – had been a director of Woolwich Arsenal prior to their decision to abandon the district in 1913 and was a cousin of ex-Gunners’ chairman John Radford.

This surely gives new weight to the importance of Arsenal’s departure to Charlton’s emergence as a professional club after the First World War.

I checked and came to question the club’s contemporaneous account of the background of 1980s director Chief Francis Nzeribe. And I blurred an apparent inconsistency in the original book about the number of seats in The Valley’s former west stand.

More sombrely, I updated the number of those who died at Hillsborough to include coma victim Tony Bland, who became the 96th fatality in March 1993.

The ramifications of that 1989 disaster and others that decade at Bradford and Heysel were manifest in obstacles that lay in the way of The Valley. In 1991, however, Charlton fans could still watch matches from the terraces of the Boleyn Ground and the imposition of all-seater stadia by Lord Justice Taylor had yet to find widespread acceptance.

Even the possibility of settling drawn games via a penalty shoot-out, as loomed into prospect for the 1987 play-off final replay against Leeds United, was regarded with incredulity by then manager Lennie Lawrence.

Another incongruity for younger readers is likely to be the emphasis on the role in the club’s affairs played by the local press, which was a much more important source of information and agent in spreading awareness of issues than it is now.

I am, of course, biased, because from 1989-98 I reported on the club for the Mercury, but I do not think I am wrong about the influence it then held.

It was, after all, the 15,000-signature Mercury petition initiated by sports editor Peter Cordwell that sparked the campaign in 1986 and it was certainly the paper’s coverage in 1990 that helped to legitimise and disseminate the Valley Party message in the local elections.

Even in 1991 the first club website was still four years away and Sky Sports News did not launch until 1998, never mind Twitter, Facebook and YouTube.

Not everything in the media landscape has changed, mind you. The Evening Standard was hostile and useless, even then.

When I had finished revisiting the book as it was first published, I turned my attention to the 14 months or so that elapsed between the end of the original narrative and the return home.

In October 1991, Richard Murray and Martin Simons had been directors for just six months. Thus far the steps back to The Valley had been led by chairman Roger Alwen and vice-chairman Michael Norris, but it was not insignificant that the new men’s pictures featured on the final page of the text.

While Alwen remained centre stage as chairman until 1995, it was Simons and Murray who worked closely with the supporters to deliver the return over the final year.

This was most obviously through the mechanism of the Valley Investment Plan, which raised more than £1m towards the building work.

Meanwhile, other alliances fractured. Voice of The Valley’s Steve Dixon and supporters’ club chair Roy King joined the football club staff in the summer of 1991.

Shortly after the start of the new season, the Valley Party’s Mark Mansfield and Richard Hunt usurped former commercial manager Steve Sutherland and his co-host Clive Richardson’s Sunday night Charlton slot on local radio station RTM.

Then club shop manager Chris Tugwell hijacked the supporters’ club’s away travel service with the collaboration of long-serving coach organiser Bill Treadgold.

Both disputes were under way by the time Battle for The Valley originally went to press, but were rightly – in my restrospective view – omitted. It is only with hindsight that the significance of the travel war – which culminated in Wendy Perfect being employed by first the supporters’ club and later the football club – and the longevity and popularity of what eventually became Charlton Live can properly be understood.

More importantly, this period saw the development and early success of the new managerial duo of Steve Gritt and Alan Curbishley. And notwithstanding the friction with some of the staff, the seeds of an enduring and productive partnership between directors and fans were laid.

On and off the pitch, the pattern was being set for the next 15 years, which would bring unimaginable success. There were even the first coach services to home matches from Kent.

Finding a voice for the new chapters that was consistent with what I had written 23 years earlier was itself a challenge. I was, inevitably, more reliant on what I and others had recorded at the time and less able to depend on first-hand recollection.

Sadly, of course, there was no Colin Cameron, ever willing to offer up some juicy morsel of historical information from his own files, to call upon this time.

But it was an opportunity for me to pull together the facts of the final months into what is hopefully a coherent narrative.

And it was a chance to acknowledge those, like the volunteers who helped paint the ground in 1992, whose role might have been overlooked by history, as well as to properly reflect the important part eventually played by Simons and Murray.

Finally, I included a new introduction and contemporary articles by me from both the Valley Review and the Mercury.

Battle for The Valley was well received in 1991 and its 3,000 copies have been sold out for 20 years, but it has always been unfinished business to me. I hope it will find a new audience and that at £9.99 a part of the old one will want to embrace it too.

It is my book, but it is not my story. The history belongs to all of us. It is part of what makes us the club we are and it always will be.

We should all be proud of that.