Roland is a record-breaker, but not in a good way

by Rick Everitt

This article was originally published in VOTV143, published in April 2018.

As several hundred Addicks fans marched through the streets of the Belgian town of Sint-Truiden in March 2017, the object of their ire, Roland Duchâtelet, was entertaining visitors from Germany in the security of the Stayen complex that is the home of the local football team. He had no cause to worry about Charlton, he told the representatives from Carl Zeiss Jena, according to one of those present. After all, he had recently made about 16 million euros selling the SE London club’s players.

It was a telling exchange, both in terms of Duchâtelet’s chosen measure of success and the half-truth which the Charlton owner’s boast represented. As the club’s

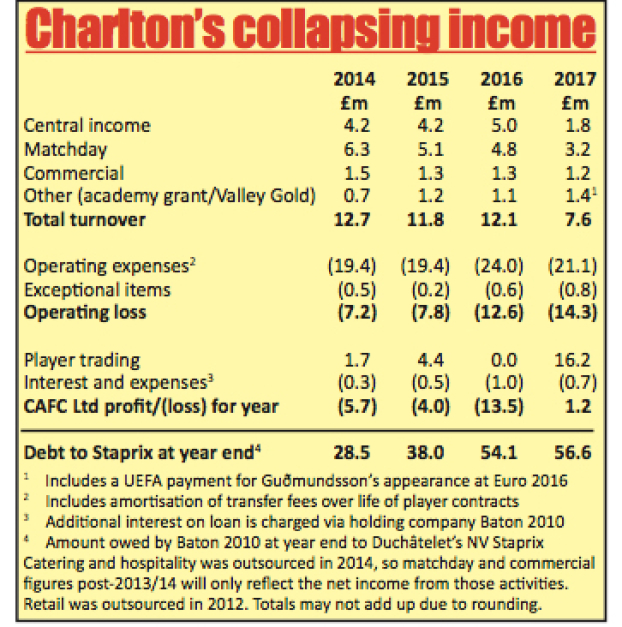

newly released 2016/17 accounts have now revealed, the Addicks did indeed show a profit on player trading last season of £16.2m, easily a Charlton record. Ademola Lookman’s move to Everton in

January 2017 will have been the biggest contributor to that figure, alongside Jóhann Berg Guðmundsson and Nick Pope’s switch to Burnley in the summer of 2016. Other fees were received for Jordan

Cousins, Morgan Fox, Callum Harriott and Tareiq Holmes-Dennis. Since none of them arrived at The Valley with a transfer fee attached, their entire sale value is shown in the books as

profit.

The accounts note that the club also received payments from previous transfers, notably for Carl Jenkinson, who left for Arsenal as long ago as 2011. The fact that

Joe Gomez, who moved to Liverpool in 2015, did not make a Premier League appearance in 2016/17 following his cruciate ligament injury probably means his sale did not contribute, but that will change

in 2017/18.

Unfortunately for Duchâtelet, however, this huge transfer windfall was largely offset by an enormous operating loss of £14.3m – even beating the £12.6m the Belgian had

achieved the previous season, when profit on player trading was zero.

“For the first time in 13 years the company made a profit,” reports departed chief executive Katrien Meire in a quaintly upbeat commentary to the accounts, a flavour of

which is given by the aside: “Right at the end of the season in April, the side showed the promise of things to come.”

Given that Kark Robinson’s team had managed to beat three of the eventual bottom five and draw with another, I suppose she has a point. At least, this time, the report

did not discuss the academy above the first team. But even Meire had to acknowledge that “2017/18 will not see this level of player sales repeated and it is likely to be a long time before such

levels are repeated again”.

A more sanguine summary might have acknowledged that there is, on the other hand, every probability of another very substantial operating loss, since none of the

fundamentals driving it have changed dramatically since last June. But that, of course, would require Duchâtelet to face up to how empty his boast to the Germans had been.

In fairness, Charlton have recorded an operating loss every year since 2005 and there is a school of thought that says the club has been lucky to have an owner with the

personal wealth to underwrite it with loans from Belgian parent company Staprix NV. That liability had grown from £18.6m in January 2014 to £56.6m by June 30th, 2017, and has more than likely

increased by up to £10m more since.

The problem with such an argument is that Duchâtelet’s own mismanagement has significantly exacerbated the problem. In the five years prior to 2015/16, Charlton’s annual

operating loss was between £6.1m and £7.8m. In the last two published years, and no doubt again in 2017/18, it has ballooned to nearly twice that, while the team went backwards.

It’s hard to see why we should be grateful to him for adding debt while running the club into the ground – especially if he is expecting to be paid back with interest on top when he sells

it.

At least that interest rate was dropped from 3 per cent to 2 per cent from July 1st, 2016, meaning the football club accounts only include £695,000 this time around. That

left an overall profit of £1.2m, but the total debt still rose by £2m. As before, interest is charged on the £18.6m part of the debt – effectively the cost of buying the club in 2014 – only in

the accounts of holding company Baton 2010 Limited, which bring together Charlton Athletic Football Company Limited and Charlton Athletic Holdings Limited, which owns the freehold

property.

That charge took the total interest for the year to £1.1m, and reduced Baton’s profits to £827,000. Despite this the debt to Staprix rose by £2.5m, some of which was accounted for by an increase in cash held at the year end and some by capital expenditure, much of which was to benefit the community trust and Footscray Rugby Club.

The report notes that staff costs dropped from £14.1m to £11.1m following Charlton’s descent into League One, but in fact 2015/16 had itself been an exceptional

year.

The comparable figures in the three preceding Championship season were £12.0m, £11.5m and £11.5m. In 2011/12, Charlton’s League One staff costs were £8.9m (including player promotion bonuses). In

2010/11, they were £7.5m. Even allowing for some wage inflation, it’s clear that in 2016/17 Charlton had a Championship wage bill in League One.

If you could strip out the administration and academy staff, the excessive level of pay would be even more stark. And, as you won’t need reminding, the team only finished

13th.

That £11.1m figure for last season is without including an (anything but) exceptional item of £779,000 for “staff restructuring” – likely to have covered paying off sacked manager Russell Slade and

his assistant Kevin Nugent, as well as the unwanted El-Hadji Ba (17 months outstanding), Zakarya Bergdich (three years outstanding), and the apparently crocked Alou Diarra (who immediately joined

Nancy).

“Key management compensation” rose from £838,761 in 2015/16 to £965,748. Likely to cover the first team managers, academy boss Steve Avory, Meire, then finance chief

David Joyes and chief operating officer Tony Keohane, plus possibly club secretary Chris Parkes, the 2014/15 figure was £685,030 – so there has been a 41 per cent increase in two years. The most

likely explanation is that Slade and Robinson were paid considerably more than Bob Peeters, Guy Luzon and Karel Fraeye, in particular.

Meire’s personal compensation is again not identified as directors’ remuneration on the spurious basis that she was only paid as chief executive. I continue to believe

that this is a breach of the regulations under the Companies Act, as do people far more qualified than me.

On the other side of the financial equation, income fell sharply as attendances plunged by 29 per cent. Charlton’s turnover was down to a meagre £7.6m, the club’s lowest

since 1998. The overall salary bill was 146 per cent of turnover, which is off the scale.

A £3.2m decline in central revenues (Football League television money and Premier League solidarity payments) was the inevitable consequence of relegation from the

Championship, but matchday revenue (principally season and match ticket sales) also collapsed from £4.8m to £3.2m.

That too might just appear the predictable consequence of relegation, except that the 2015/16 figure was already the lowest, again, since 1998. In both years, it reflects

deep supporter discontent, as well as failure on the pitch.

Matchday revenues in the season Duchâtelet arrived, swollen by the 2014 FA Cup run, were £6.3m. But following a restructuring of ticket prices they were £5.1m in 2014/15,

a figure they also hovered around during Charlton’s three League One seasons between 2009 and 2012, albeit they would then have included all the matchday catering income, not just any profit handed

over by contractors.

Meire argues that the club did well to retain £1.2m in commercial income despite relegation, but that has to be put in the context that Charlton’s figure was already one

of the lowest in the Championship.

If the historical background isn’t revealing enough, how about a comparison with neighbours Millwall, a similar but traditionally smaller club? Admittedly, their

2016/17 season culminated in promotion from League One via the Wembley play-off final and an FA Cup run that only ended in the quarter-finals, which were bound to boost their finances, but generally

they operated in a similar business environment with the same central payments.

Millwall’s turnover was £10m, a third more than Charlton’s; their matchday income was £5.2m, 60 per cent more than Charlton’s; their commercial income was £2.0m, two

thirds more than Charlton’s; and their staff costs (including player promotion bonuses) were £9.4m, 15 per cent less than Charlton’s. Millwall’s operating loss was £4.0m.

In other words, the board and senior management team at The Valley was as comprehensively thrashed off the pitch by the neighbours as the players were on it. Now that is

embarrassing. To add insult to injury, Millwall’s chief executive from October 2016 was, of course, Steve Kavanagh – who held the same role at Charlton until mid-2012.

Extra half-million paid out in second half of 2017

Charlton paid out £497,771 in “transfer costs, termination payments and agency fees”

between June 30th, 2017, and the accounts being signed off on December 20th last year.

Of the 2017 summer recruits, Tariqe Fosu and Billy Clarke were both signed before the

financial year end, and signing-on fees paid to free agents like Mark Marshall and Ben Reeves are not included here.

Loan fees for Ben Amos and Jay Dasilva would be included, but the nod to “termination payments” suggests a chunk of this total may well have gone to Jorge Teixeira when

he moved to Sint-Truiden in July 2017. The club also records that it received £337,600 from the sale of players in the second half of 2017, most likely to be accounted for by Lee Novak and Tony

Watt, who joined Scunthorpe United and OH Leuven respectively.

It’s not clear whether there were any contingent payments from older deals within that figure, which could include fees for Teixeira and Cristian Ceballos’s moves to Sint-Truiden, then owned by Roland Duchâtelet.

Notwithstanding the recent disclosure that Meire failed to include a sum for international

appearances in Nick Pope’s sale to Burnley, further fees payable to Charlton based on domestic appearances, caps or other on-field success leapt from £4.65m at the 2016 year end to £8.58m 12 months

later, with Ademola Lookman an obvious source.

Sums potentially payable to other clubs on the same basis dropped from £1.96m to £1.15m. Sell-on clauses are not included here either way, because they cannot be quantified in advance.

Changes to the book value of the squad suggest Charlton paid as much as £1.4m to sign Zakarya Bergdich from Valladolid and El-Hadji Ba from Sunderland in 2015.

They also imply that it cost up to £421,000 to buy Josh Magennis, Billy Clarke and Jake Forster-Caskey.

Magennis was a Slade signing, but the latter two arrived under Karl Robinson. All have been rather better value than Ba or Bergdich, who mustered just 30 senior starts between them before being paid

off.

Charlton paid out £425,466 to agents between February 1st, 2017, and January 31st, 2018, the FA has disclosed. Millwall paid £311,505.