Some reflections on 20 years since Charlton hit the net...

By Rick Everitt

In 2015 you can follow the Addicks on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and Instagram. You can get the latest news from the official club website on your desktop, laptop, tablet, mobile and watch. If you don’t mind looking ridiculous you can probably find out what’s happening in SE7 through a special pair of glasses. And you can share your views on the most obscure topic, related or not, with other supporters through Charlton Life, as well as the full range of social media.You can even email the club direct - and if you’re lucky someone might reply.

But 20 years ago the only way to source Charlton news regularly when you wanted it was the expensive and therefore minority channel of Clubcall. You might get lucky with a snippet of information on Ceefax, but otherwise the distribution of information about the club was dominated by the Mercury, RTM’s Sunday night show and the necessarily spasmodic appearance of Voice of The Valley and the Charlton programme.

In June 1995 that began to change. That month saw the launch of the first Charlton website, Addicks On-line, which eventually became the club’s official presence on the internet. Although the site was the product of a happy coincidence of factors, it was hardly a trailblazer. Fans of other clubs were setting up sites at a similar prolific rate to the emergence of the first fanzines seven years earlier. But the pioneers of the Charlton site had unusually privileged access to content.

I was both sports editor of the Mercury and secretary of the official supporters’ club, as well as editor of VOTV, while Tom Morris was the club photographer. By coincidence we had both previously worked as computer programmers, so we had an affinity with the technology. But the more significant technical input came from Glynne Jones, a fellow member of the CASC committee. Indeed, Glynne would later work for the club, overseeing its IT, as well as maintaining a mailing list from 1996 that anticipated Charlton Life by more than a decade and still continues nearly two decades on.

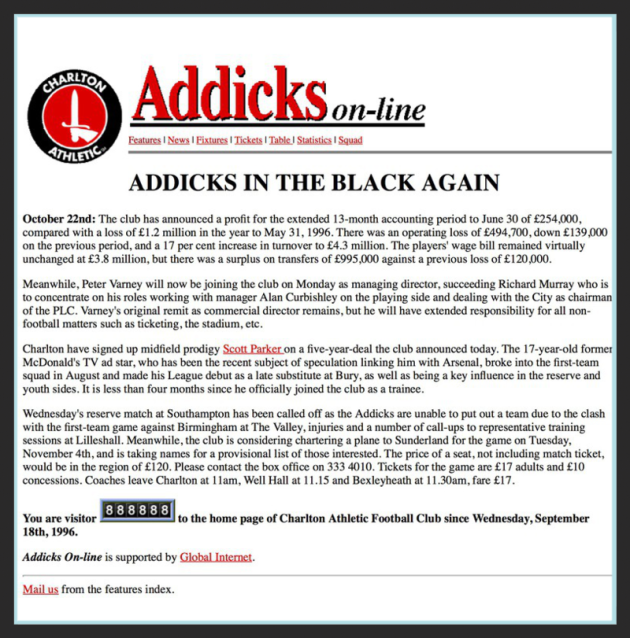

In those early years the pages themselves had to be written complete with basic HTML tags and uploaded individually to the server, together with any of Tom’s graphics. It was primitive stuff, but by a spectacular coincidence the site was officially launched through the Mercury on the same day that Steve Gritt was sacked as joint manager, June 15th, so fans could quickly read my report of the Valley press conference. Or at least the tiny number with internet access could. In VOTV66, published in April 1996, I reported that there had been 14,500 downloads of the home page in the four-month period to the end of March. But it was already clear that the rate of growth was spectacular. A year later there were 2,000 visitors a week.

A key element of what we could offer was match reports - not within minutes of the final whistle, because once the press conference was over, I was usually in the pub - but certainly by the following day. Tom would send me a selection of low-res images to illustrate the reports, which meant we were immediately able to offer a better service than the local press. None of those papers had a presence on the internet at that point.

The site was very quickly adopted by CASC as its own - the first home page was www.demon.co.uk/casc, although it soon became www.charlton-athletic.co.uk — and two years later in 1997 the football club assumed responsibility for paying the bills, although the content was still produced by us on a voluntary basis.

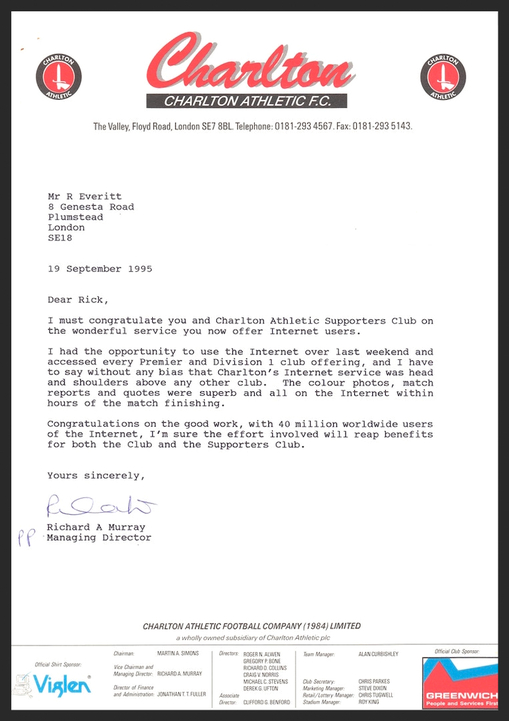

PLC chairman Richard Murray - whose brother Jan was in the IT business - had been an early enthusiast, but the club at that point had no full-time communications staff and as part-time press officer Peter Burrowes would admit he was in no way equipped to contribute to it. The fragility of the arrangements was proven, however, by the 1998 play-off final, when squeezed between the post-match celebrations, my work on the Mercury and a midweek holiday flight I could simply find no time to provide an online report of the club’s biggest game in 40 years.

Earlier that season, another familiar Charlton internet name - Wyn Grant - had stepped into the breach to cover several matches for the site while I was in America. Wyn, indeed, was one of the other pioneers, beginning his long-running Addicks Diary in 1997. By then Australia-exiled photographer Brian Cassey - who in the early 1970s had taken Charlton action pictures for the local press, plus father and son Dave and Joel Roberts, two other fans - Ben Johnson and Kevin Baxter - and Hastings and Bexhill CASC also had sites and these were displayed as links.

Promotion to the Premier League in 1998 changed much about the club and the official website proved no exception. Since I was recruited to establish a communications department, the site became wholly part of the club, media interest in Charlton exploded to an unprecedented extent and in that first season I was soon able to call on new colleagues Rachel Kleinman and Jeanette Earl for support. In 1999 Mick Collins was appointed to take specific responsibility for the site, and he was later succeeded by Lindsay McCombie, although I remained in overall charge of it until 2003, after which I switched to focusing mainly on marketing work.

By then the main URL was www.cafc.co.uk and the site had a dramatic new look. Soon after promotion to the Premier League we had been approached by a Cambridge-based firm looking to establish a reputation in web design and in early 1999 a more sophisticated look replaced the original template. By now we were uploading audio and beginning to experiment with video, with shirt sponsors Redbus supporting match highlights from 2000, although facilities at The Valley remained limited and were not helped by the fact that the communications team was first shunted out to an industrial estate off Bugsby Way to allow for extra hospitality space and then, with other staff, removed to Bexleyheath.

Matt Wright was recruited as assistant communications manager in 2000 and one of his main duties for the next decade was to produce a daily plain text email bulletin that was sent to thousands of subscribers. It was originally intended to drive traffic to the site, but soon developed a life and identity of its own.

By 2002 the club wanted to exploit potential income streams from gambling and advertising, entering into a partnership with a larger firm to host the site, but the relaunch was plagued by technical and other problems. The commercial revenues did not materialise either, so in 2004 a further switch was made to Surrey-based Digital Ink, who remained the club’s reliable main providers until 2010 and continue to facilitate online ticket sales and some retail pages via the online commercial centre nearly five years later.

One disappointment is that the discontinuity between providers - and the more commercially driven agenda that has partly motivated the changes - has obstructed the development of a reliable and easily accessible archive. By now that would have been a valuable resource.

The big switch came in late 2010 when the board opted into the FLi (Football League Interactive) set-up, which had been formed in 2004 to try to maximise internet and mobile rights for the clubs below the Premier League. In Charlton’s very difficult financial circumstances at the time, the commercial logic had become overwhelming. Some of the initial concerns then expressed inside the club have since been overcome by a significant improvement in the design of the FLi sites.

In any case, the world has moved on. The Charlton Life message board, launched in 2006, has arguably become a more important site than the club’s own, since it acts as an efficient clearing house for much more than the narrow official perspective on the club’s affairs, while many find social media a more convenient way to keep in touch. The official site can also be slow to report developments because of other pressures inside the club and the need to be authoritative. A variety of bloggers add another dimension.

It’s doubtful if anyone would want to go back to the days when far-flung supporters had to wait for me to get home from the pub - and usually to sober up too - before they could get detailed news of events at The Valley. But it was exciting to be there at the beginning and even then you could be confident you were part of something that was going to change Charlton. What we didn’t realise was the extent to which the internet would also change the world!